Art Song of Williamsburg

Barbara Quintiliani, Bel Canto and Verdi,

Art Song of Williamsburg Opens a New Season

On November 5, 2004 in Williamsburg, Virginia, to a full house and with Charles Woodward at the piano, Barbara Quintiliani gave a stunning recital of art songs and arias by the bel canto era's major opera composers. In conversation at the elegant reception we met Barbara's current teacher, Anna Gabrieli of Boston, and asked her to share with our readers her reaction to this wonderful concert. The opening song by Benedetto Marcello (1686-1739), il mio bel foco; Quella fiamma (The fire in my breast; the flame) from the baroque period has a special place in their ten year history. Ms. Gabrieli tells us "I think back to the moment in 1994, when I first heard Barbara as a freshman at the New England Conservatory. She stood on a small stage with a sweater tied around her waist and sang one of the 24 Italian Songs, which we all learn as beginning singers. The way she sang that song, it became a major operatic aria (which it was when it was written)! I knew I was listening to a young woman who would become an operatic star. That aria was Benedetto Marcello's Quella fiamma." Barbara had recently graduated from the Governor's School for the Arts in Norfolk where she had been taught by Sondra Gelb, Alan Fischer and Robert Brown who were in the audience to see how their star pupil sings now.

Some four years later, when Barbara was having trouble with her highest notes, she sought help from Ms. Gabrieli who continues "In 1998 Barbara became my student and in a few months, won both the Metropolitan Opera National Auditions and the Marian Anderson Competition at 22 years of age. She has worked hard with her brilliant voice, her acute musical intelligence, and her innate artistry to surmount many important hurdles since then."

There followed Antonio Vivaldi's (1675-1743) best known aria Sposa son disprezzata (Ever loving, I am scorned) from the opera Bajazet and Gioacchino Rossini's (1792-1868) Preghiera di Anna: Giusto ciel in tal periglio (Merciful heaven, in such danger) from Maometto II. Her lushly passionate delivery showed a growing maturity of voice; from the superb high notes down to the mezzo range, her legato was impeccable.

Her second set was a fascinating piece of musical history, well worth recounting here. The first song, Parad! (Stop!), was written by a Spanish tenor, Manuel Garcia, Sr. (1775-1832). Rossini wrote the role of Almaviva in The Barber of Seville for Garcia, who first sang it in Rome and later in Paris, London and New York.

Three of Garcia's children became famous. His son, Manuel Garcia, Jr. (1805-1906) was a baritone who, after a singing career established a music school where he taught numerous students who became internationally famous singers. His most notable contribution was the invention of the laryngoscope in 1855. Maria Felicitá (1808-1836), under her married name, Maria Malibran, was a favorite of bel canto composers. Her composition, Il Mattino (Morning) is a joyous, romantic description of nature by a woman very much in love with bird warbles and the bleating of lambs which were woven into both voice and piano parts. Her sister Pauline (1821-1910), under her married name, became the very famous mezzo-soprano Pauline Viardot, whose song Moriro! (I Shall Die!) is a diva's showcase with a text of epic self-pity.

In this set, Ms. Quintiliani regaled us with lush lyrical singing, beautiful vocal colors and honest intensity when needed.

She closed the first part of the program with the aria M'odi, ah m'odi from Lucrezia Borgia by Gaetano Donizetti (1797-1848). Not just the voice but the whole person created the role of a mother pleading with her son to drink an antidote to the poison she put in the party drinks for revelers, only to learn that one of them is her son. He refuses, preferring to die with his friends.

This singer's clear diction and high notes could shatter crystal! The intense solo piano part gives the singer a brief break. The mother's horror at knowing she has destroyed her son's life ends in an unbelievable cry of pain.

After intermission we had songs of the bel canto period. Since there were no lyric poets in the Italian tradition, the texts are direct as is the emotional intensity. Tears are called forth by the ending of Vincenzo Bellini's (1801-1835) L'abbandono (Abandonment). Vaga luna, che inargenti (Lovely Moon) creates pathos for a lover alone in the moonlight. In Per pieta, bell'idol mio (For pity's sake, my Goddess) continues the sad mood, "I languish under your gaze…" The set closes with a song of devotion to the beloved, Ma rendi pur contento.

In the final set of songs, by Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901), our singer revisited two songs she sang in Norfolk in May of 2000. Il tramonto (Sunset) and La zingara (The Gipsy Girl). In that time her voice has grown, adding a richness in low notes that is necessary for a full realization of Verdi and as Ms. Gabrieli describes it so well: "As I listened to her in Williamsburg, what struck me most was the realization that she was now truly mistress of that stage and of her program. There was a maturity and security in her presence that I had not seen before. She was, of course, brilliantly supported by Charles Woodward's beautiful playing. She was also singing to a loving audience."

The song Non t'accostare all urna (Do not approach the urn that contains my ashes), is a miniature opera with creamy piano lines against the smoldering intensity of her restrained delivery. In solitaria stanza (In a secluded room) is the story of the supplication "to merciful gods" to save a beautiful woman who is dying. The last song, Brindisi (A Toast) is a hymn of praise from Verdi's heart - an experience captured in the voice, celebrating the honest pleasure of a glass of wine.

The last selection was Involami from Verdi's Ernani. We will let Anna Gabrieli have the last word: "The concert contained a lot of music that was new for her, and included her first performances of the arias from Donizetti's Lucrezia Borgia, and Verdi's Ernani. I felt she gave them stunning debuts and showed us all that she is, or will soon be, the new bel canto and Verdi singer for which the operatic world has been waiting." The near roar from this usually sedate audience at the end of the song was entirely appropriate. She is that good!

When we saw Genevieve McGiffert, artistic director of Art Song of Williamsburg, a few days later, we were still raving over the beauty and richness of Barbara's low notes, her most recent development. Thanks to Genevieve and her fine organization we have had the opportunity to hear Barbara in both January 2002 and November 2004.

Britten Britten's Winter Words in Williamsburg

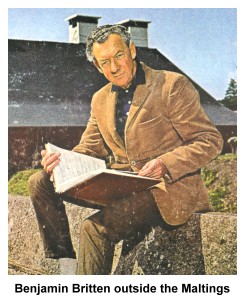

It was Saturday evening, June 7, 1969

and Michael and Genevieve McGiffert were in Snape, England for the opening concert of the

Aldeburgh Festival. At 3 pm they were in the audience at the Maltings

Concert Hall for a chamber concert by the Amadeus Quartet, which included

Schubert's Trout Quintet with Benjamin Britten playing his

beloved Steinway piano. In the evening they saw an opera performance

and walking back to their lodgings across moonlit wheat fields, they

looked across to see a great ball of fire in the distance. The Maltings

was burning. Only two years before the hall had opened in a converted

historic brewery building.

At the time Genevieve was working on her doctoral dissertation, the main subject being Britten's opera Peter Grimes and was scheduled to visit him the later that week. To their surprise, she and Mike were able to have sherry with Britten and his sister at "The Red House", his personal residence. "We mostly discussed Peter Grimes", said Genevieve of the " memorable occasion." According to Britten's biography by Humphrey Carpenter, immediately following the fire, Britten's attitude was one of determination that the Maltings would be rebuilt, incorporating improvements in design learned from the first building experience.

This story was shared with the audience at Art Song of Williamsburg's

January 28, 2005 recital, during the opening talk by Genevieve McGiffert.

Tracey Wellborn, tenor and Tamara Sanikidze, piano were the featured

performers in a program titled Love, Innocence and Experience.

The richly designed program included Adelaide by Beethoven

(1770-1827), the complete Dichterliebe cycle of sixteen songs

by Robert Schumann (1810-1856), five selections by Charles Ives

(1874-1954) and Britten's (1913-1976) Winter Words. The communication

of these excellent performers with each other on stage offered us

an outstanding experience of the art of song. Genevieve commented

to the audience at intermission that this was the best Dicterliebe

that any of us are ever likely to hear!

This story was shared with the audience at Art Song of Williamsburg's

January 28, 2005 recital, during the opening talk by Genevieve McGiffert.

Tracey Wellborn, tenor and Tamara Sanikidze, piano were the featured

performers in a program titled Love, Innocence and Experience.

The richly designed program included Adelaide by Beethoven

(1770-1827), the complete Dichterliebe cycle of sixteen songs

by Robert Schumann (1810-1856), five selections by Charles Ives

(1874-1954) and Britten's (1913-1976) Winter Words. The communication

of these excellent performers with each other on stage offered us

an outstanding experience of the art of song. Genevieve commented

to the audience at intermission that this was the best Dicterliebe

that any of us are ever likely to hear!

Michael McGiffert wrote the program notes for Winter Words. He and Genevieve honored our request to share their insights with our readers. Their only caveat was that we direct readers to an article from The Musical Times in 2001 by the English critic Wilfried Mellers that they found insightful.

This set of songs titled Winter Words, Lyrics and Ballads of Thomas Hardy includes eight poems selected by Britten contrasting innocence with experience. Genevieve told the audience, "Even though they are not Hardy's greatest poems, which are usually too rhythmically and emotionally subtle to need projection into sounds other than those of the speaking voice, they are choices germane to Britten's purposes." While Mike wrote, " Each of these poems tells a little story. Each story has about it a touch of mystery--of nature or of humanity or the two intertwined. Most are also, in some sense, a kind of argument for heightened consciousness; they reflect upon the rolling of time, on life as a journey, on the loss of innocence, on youth and age, world and spirit."

Back to Genevieve: "The first poem, At day-close in November, is something of a prelude. The rhythm of the verse accords with the bleak landscape, making for a calm acceptance of impervious Time's threat to childhood's innocence. 'Old' Hardy, knows how long ago those trees were planted, but the young ones don't, their happiness lying in their ignorant unknowingness. Britten's musical images are precise. Although the verse's pulse is slow and weary, the music is 'quick and impetuous', like the children's frolicking, where the dissonance and the dislocated or syncopated rhythms of the piano enact both the wind-blustered swaying of the trees and the agitation within the aged poet's heart. "

Mike again: "Innocence is not perhaps an unqualified good. The lonely boy on the night train traveling toward an unknown destination and destiny in Midnight on the Great Western is in a state of unknowing-'listless,' 'incurious'--that is closely akin to simple ignorance. He does not seem the type to have 'spacious visions' of a heavenly sphere above 'this region of sin.' Death lies at journey's end; the boy--humanity in small--will come to it without much having lived."

Mike continues: "Wagtail and Baby Hardy called a satire. Well, perhaps it is, for satire runs shallow but cuts deep, and this little poem goes, in its jokey way, to the heart of one of the cycle's great themes. Here is a generic baby, innocence in repose, and there, in the stream, is a bird, innocence at play, nesciently minding its own business of dip and sip and prink, insouciant. The baby is thoughtless; it does not know it does not think; it is all eyes. The scene is a kind of Peaceable Kingdom: big beasts may blare and slink but do no actual harm to either bird or baby. We are in the land of fable; fables have morals: that is their reason to exist. Even the 'perfect gentleman' who shatters the scene has a part in this morality play. His perfection is that of civilized society; his gentility is the badge of experience. He will no doubt drive off the beasts, but he also scares away the wagtail. Eden had really no place for gentlemanly perfection. When the wagtail takes flight, paradise passes."

Genevieve: "The next number, The little old table, is another 'satire of circumstance' that complements the previous one in that it is not about a baby but about an old man (Hardy himself), remembering. Although the poem is bleakly about non-communication, this is not because memory is dimmed but rather because it is too acute. Britten captures this by making his setting the most 'realistic' song thus far, since the creaking of the table becomes the substance of the music. The piano part enunciates the 'creak' in off-beat quarters in 2/4 time making the creaks bumpily spasmodic." Mike continues: "The Little Old Table that creaks so audibly in Britten's setting of the fourth poem …, with the added piquancy of the speaker's failure to 'understand' the thought behind the original gift and, we may believe, the price hence paid in loss of love."

Genevieve: "The next number, The choirmaster's burial, is the longest song and forms the climax to the cycle, being a ballad in the basic sense that it tells a psychologically complex story." When the choirmaster dies, our narrator, the tenor, wishes to honor his request to have his favorite hymn played at the graveside, to ease his passage. The vicar is in a great hurry and chooses a read service. But the vicar observes blithe spirits all white in the graying evening twilight granting the choirmaster's last request.

"The next number has no human population and neither tells a tale nor recounts a specific incident. Proud Songsters is not narrative - it is physically descriptive, capturing the burgeoning present. The birds's chattering trills create a sonority that is richly scrunchy, sap-filled, as those loud nightingales chortle away to their bursting hearts' content, 'as if all Time were theirs'. On this phrase the voice expands in a joyous melisma, though at the same time the shimmering seconds become unstably chromatic, since the bird's time is not really forever, except in the sense that they don't know that it isn't. Britten, based on Hardy, indulges in no retrospection but simply accepts Nature's fecundity."

Genevieve continues:" From Nature's unconsciousness we return for the seventh song to the all too human predicament, and to a poem that exactly balances the second poem. At the railway station, Upway is both a moment of vision and a satire of circumstance, taking us back to the song about the Journeying Boy in the railway carriage, but presenting a still clearer dichotomy between innocence and experience." Mike continues her thought: "Experience and innocence come face to face in the grimly gleeful convict being knowledge in handcuffs, the 'pitying child' bringing the gift of the innocence of grace. But the outcome is ambiguous: the constable in charge only smiles, does not speak, seems 'unconscious of what he heard.' But we know he is not: whether as God or as the thinking poet himself, he holds the moral of this passing moment."

Mike continues: "The last poem, Before Life and After, is the most boldly argumentative, a kind of sermonette. Each of the others in its various ways is, in effect, a commentary of experience upon innocence. The effect is that of perhaps-unintended irony. The poet mourns the loss of 'primal rightness'--the passing of Eden--and laments the 'birth of consciousness'--the denaturing (as it were) of human sentience. He longs for the reaffirmation of 'nescience.' But nescience does not make poems, or moralize experience, or reflect upon itself. Nor, one might add, does it sing. [But] Britten's picking and ordering of these poetic gems--variously touching and tough, passionate and ironic--wonderfully serves, and at the same time transcends, Hardy's glances into human experience--the insights, we may say, of a deep-seeing and far from simply innocent eye. These poignant poems and this marvelous music, fused in the art of song, are a remarkable triumph of artistic consciousness."

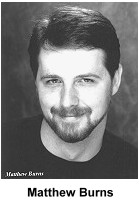

Matthew Burns and Melanie Day

Close

Art Song of Williamsburg's Fifth Season

Art Song of Williamsburg ended their season with a terrific recital celebrating the 400th Anniversary of Miguel Cervantes' novel Don Quixote. The friendly, approachable Matthew Burns, bass-baritone, sang an excellent program, his first professional recital. He had previously concentrated on building a career in the opera house and on concert stages but his talent shone brightly in Spanish and French art songs. He was well partnered by professional coach-accompanist Melanie Day at the piano.

The program, titled The Impossible Dream, was introduced

by Dr. Genevieve McGiffert, who spoke to us about "Our Spanish Inheritance"

where she pointed out that Don Quixote has been the subject of some

seventy operas and a number of art songs, including Seite canciones

populares Españolas by Manuel de Falla (1876-1946). This is

a cycle of seven songs that use Spanish folk texts and familiar

Spanish dance forms to create songs of depth with a popular appeal.

There are lovely solo piano sections and they give the singer an

opportunity to demonstrate a wide range of emotional, as well as

vocal, expression. In Enrique Granados' El majo olivadado

(The Forgotten Suitor) we have a lyrical, lovely song of great drama,

fully captured by our performers.

The program, titled The Impossible Dream, was introduced

by Dr. Genevieve McGiffert, who spoke to us about "Our Spanish Inheritance"

where she pointed out that Don Quixote has been the subject of some

seventy operas and a number of art songs, including Seite canciones

populares Españolas by Manuel de Falla (1876-1946). This is

a cycle of seven songs that use Spanish folk texts and familiar

Spanish dance forms to create songs of depth with a popular appeal.

There are lovely solo piano sections and they give the singer an

opportunity to demonstrate a wide range of emotional, as well as

vocal, expression. In Enrique Granados' El majo olivadado

(The Forgotten Suitor) we have a lyrical, lovely song of great drama,

fully captured by our performers.

We were presented Maurice Ravel's (1875-1937) Trois Chansons de Don Quichotte (Three Songs of Don Quixote), which were finished too late to be used in a French film on the Don's adventures. Jacques Ibert (1890-1862), a younger contemporary of Ravel's was asked to compose the songs when Ravel was late. We also heard his

Quatre Chansons de Don Quichotte. The film stared the famous Russian bass Fyodor Chaliapin, of whom the program states that the 1933 recording is willful and inaccurate in every particular. Fortunately we heard Matthew Burns give a very convincing performance of music that for him "embodies the spirit of this chivalrous knight," and his adventures on behalf of his lady whom others see as a strumpet. The pathos of the Chanson de la mort (Song of the Death of Don Quixote) was very moving. They ended the recital with three songs from Man of La Mancha by Mitch Lee (b. 1928): I, Don Quixote, Dulcinea and The Impossible Dream.

Another special treat was an aria from a zarzuela - the Spanish equivalent of an operetta. These two pieces by Pablo Sorozábal (1897-1988) are from La tabernera del Puerto (1936) and demonstrate the composer's acerbic wit. The text of the first songs admonishes the black man to make up - "you get beatings while your master gets fat" and the second is about men who love women indiscriminately.

Throughout the recital there were opera

arias of power and persuasion. The program opened with Non più

andrai from Le nozze di Figaro by Mozart. Later we heard

La calunnia, from Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia

(1816), about how gossip travels around from person to person. The

first set closed with Toreador Song from Carmen by Bizet.

The second half opened with two arias from Jules Massenet's (1841-1912) Don Quichotte which gave the flavor of the adventures of this unfortunate idealist and his devoted Sancho.

The encore found Mr. Burns inviting everyone present to join voices in a happy reprise of The Impossible Dream. Sing we did, bringing to a close another excellent season of art song in Williamsburg. Watch our calendar for season six concerts.

The Performers

If, for the moment, we ignore the international aspect of her career, Melanie Day has impressive credentials teaching both history of art song and serving as a vocal coach at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia, where she is Director of Opera Theater in the School of the Arts. Ms. Day's former students are now singing at opera houses throughout the world. As a coach/accompanist she has played at Carnegie Hall, Washington National Cathedral, Austria, Italy, Costa Rica and South America.

Matthew Burns made his New York City Opera debut in 2002 and has since been seen in roles in Of Mice and Men, Little Women, The Rape of Lucretia, Gianni Schicchi, Madama Butterfly, Dead Men Walking and several other operas. In Carlisle Floyd's Susannah he played Olin Blitch, the sinning preacher, and was reviewed in the New York Times: "Matthew Burns has a beautiful bass-baritone voice. He manages the tricky feat of portraying Olin Blitch as both sympathetic and credibly bad." He has played leading roles in an impressive list of other opera houses in the United States. This summer (2005) he will travel with the New York City Opera to perform in Japan.

Printer Friendly Format

Back to Top

More ASoW

Review Index

Home

Calendar

Announcements

Issues

Reviews

Articles

Contact

Us

|